Part 81: 1960

MOVIES:

Anatomy of a Murder (hidden gem)

Ben-Hur (winner)

The Diary of Anne Frank

Room at the Top

The Nun's Story

Anatomy of a Murder

Director: Otto Preminger

Starring: James Stewart, Lee Remick, Ben Gazzara, Arthur O'Connell, Eve Arden, Kathryn Grant, George C. Scott, Orson Bean, Russ Brown, Murray Hamilton, Brooks West, Ken Lynch, John Qualen, Howard NcNear, Alexander Campbell, Ned Wever, Jimmy Conlin, Royal Beal, Joseph Kearns, Don Ross, Lloyd Le Vasseur, James Waters, Joseph N. Welch

Oscar Wins: No wins.

Other Nominations: Best Actor (James Stewart), Best Supporting Actor (Arthur O'Connell), Best Supporting Actor (George C. Scott), Best Film Editing, Best Cinematography (Black and White), Best Writing (Adapted Screenplay), Best Picture

I may have been born and raised around Chicago, but I’m a small-town girl at heart. I love the idea of everything in town being within walking distance...restaurant staff knowing what you mean when you say “the usual”…local parades that bring out even the most recluse members of the community.

My love of small-town America was one of the things that initially drew me towards Marquette, MI – home of my eventual alma mater, Northern Michigan University. The main drag was slim at the time, home to a bakery, a book shop, and a small assortment of tourist shops. Lake Superior and Presque Isle Park were within walking distance from campus, as was the Superior Dome, which is – fun fact! – the largest wooden dome in the world.

The Superior Dome was also home to the NMU football team so, being in marching band, I spent a lot of time there. The Dome features many glass cases around the exterior of the field, filled with everything from sports memorabilia to taxidermy displays of local wildlife. But my favorite display case paid homage to Marquette’s biggest claim to fame in the pop culture game (outside of Joe Pera Talks With You at least): Anatomy of a Murder.

Set and filmed in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, Anatomy of a Murder is a riveting courtroom drama and murder mystery. It tells the true story of one of the first uses of “dissociative reaction”, a version of the insanity plea, analyzing the complex makeup of a deviously intriguing killing. With jazzy music by Duke Ellington, as well as truly phenomenal acting and superb dialogue (complete with very racy word use for the time!), Anatomy of a Murder is more than worthy of its local display case – and more!

Fisherman by day, musician by night, and lawyer when absolutely necessary, Paul Biegler (James Stewart) has been offered a very unique case. Lt. Frederick Manion (Ben Gazzara) has shot and killed Barney Quill after Quill allegedly raped and beat Manion’s wife, Laura (Lee Remick).

Manion doesn’t deny the killing, but claims his actions were justified. His only defense is a bout of insanity – a condition known as “irresistible impulse”. It’s up to Biegler to prove this unsympathetic murder was simply blinded by rage.

Biegler’s folksy speech and laid-back demeanor hide a sharp legal mind and a propensity for courtroom theatrics, such as the ol’ “I’ll ask an out-of-order question that the judge will throw out but the jury will nonetheless hear and perhaps remember when it’s time to discuss the verdict” ploy. But even Biegler is no match for the new hot-shot state’s attorney, Claude Dancer (George C. Scott). As slips and discrepancies emerge, it seems Manion is not all that impulsive, his wife is not all that pure, and the victim is not all that nefarious.

The courtroom scenes alone take up the length of an average movie in Anatomy of a Murder, which luxuriates in its 160-minute run-time. This is a film that delights in the details, the time and research spent putting a case together. The entire movie is full of scenes where smart people size up one another and verbal exchanges feel more like a chess game than a conversation.

As viewers, we get to see all sides of courthouse drama, including all the antics, trickery, badgering, and spontaneous outcries. All the facts are presented to the audience – the only thing we never see is the actual murder and the events leading up to it.

Were Manion’s actions justified? The only conclusion comes from our own interpretation of what’s presented to us. The then-daring use of such words as “spermatogenesis”, “sexual climax”, “bitch”, and “panties” pales in comparison to the legitimate questions about the pros and cons of jury trials that Anatomy of a Murder raises.

Widely considered among the finest trial films ever made, Anatomy of a Murder is maybe more universally loved by law students than cinephiles. It’s not only honest in its portrayal of courtroom antics, but in the nitty-gritty of process – of research, assembling witnesses, building a case, and preparing a testimony.

It’s similar to 12 Angry Men in that way – though if 12 Angry Men serves as an example of justice and how the principle of “beyond a reasonable doubt” serves that concept, Anatomy of a Murder is a film that’s primarily concerned with the limits of the law, and how we may manipulate it to create our own form of justice.

Ben-Hur

Director: William Wyler

Starring: Charlton Heston, Jack Hawkins, Haya Harareet, Stephen Boyd, Hugh Griffith, Martha Scott, Cathy O'Donnell, Sam Jaffe, Finlay Currie, Frank Thring, Terence Longdon, George Relph, Andre Morell, Laurence Payne

Oscar Wins: Best Actor (Charlton Heston), Best Supporting Actor (Hugh Griffith), Best Art Direction (Color), Best Costume Design (Color), Best Sound, Best Music (Music Score of a Dramatic or Comedy Picture), Best Film Editing, Best Cinematography (Color), Best Special Effects, Best Director, Best Picture

Other Nominations: Best Writing (Adapted Screenplay)

At its core, Ben-Hur is basically a revenge movie, a story of two childhood friends who are constantly seeking vengeance on each other. It’s a fairly simple plot, yet this film is always mentioned in Top 10 lists of epic Hollywood films. Why?

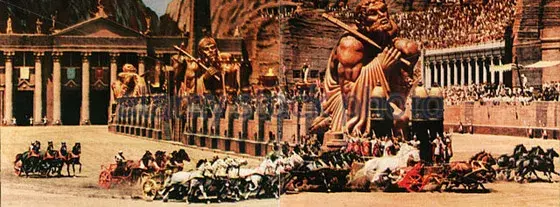

Its “epic” status is not so much driven by its plot, but by its titular set piece: the chariot race. While time hasn’t been kind to other scenes in Ben-Hur, the chariot race is one that still shocks and delights – one you watch and can’t help but wonder how they filmed it…and how everyone survived.

Ben-Hur is very much a product of its time in other ways, too. All the characters are perfectly shaven and bathed, dressed in well-pressed clothes and sporting shiny new shields and helmets. The acting is hammy, the romance is one-note, and I have yet to see a tall, blonde-haired, blue-eyed Jew at any synagogue service I’ve attended! Like many epics of the time, it’s clear telling a realistic story wasn’t as important as telling an entertaining one.

But none of that hurts Ben-Hur. In fact, this still might be the best Biblical epic I’ve ever seen (which isn’t saying much, but still!). Though the film does contain some stunning technical achievements (even if they are dated by today’s standards), it doesn’t depend wholly on sheer spectacle to engage audiences. Instead, it uses arguably the most recognizable story for its backdrop…the birth and crucifixion of Jesus Christ.

Judah Ben-Hur (Charlton Heston) is a wealthy Jewish merchant living in Jerusalem during the days of Roman occupation. While the other Jews are rebelling against the Romans, Ben-Hur is a little more chill. Sure, he’d like the Romans gone, but he’s much more diplomatic about it. In fact, one of his childhood friends is Roman – Messala (Stephen Boyd), who has just been rewarded with a military command in Jerusalem.

The two friends share a warm reunion, but things turn sour when Messala tries to talk Ben-Hur into being an informant against his own people. Ben-Hur refuses, ultimately driving a wedge between the friends. Messala is such a sore loser that he seizes on a flimsy excuse to punish Ben-Hur: when a ceiling tile falls of Ben-Hur’s house and hits the Roman governor, Messala accuses Ben-Hur of throwing it deliberately, even though he knows it was an accident. He sentences Ben-Hur to hard labor as a galley slave then, for good measure, sentences Ben-Hur’s mother Miriam (Martha Scott) and sister Tirzah (Cathy O’Donnell) to life in prison.

Understandably, Ben-Hur spends the next three years nursing one mighty grudge. When a sequence of events leads to Ben-Hur’s freedom, he begins training as a charioteer, earning himself newfound prestige.

Hoping to get back at Messala, Ben-Hur enlists as a charioteer for the wealthy Sheik Ilderim (Hugh Griffith), who suggests that the best way to get back at Messala is to hit him where it hurts: his pride. And this, dear readers, takes us to that pinnacle chariot race.

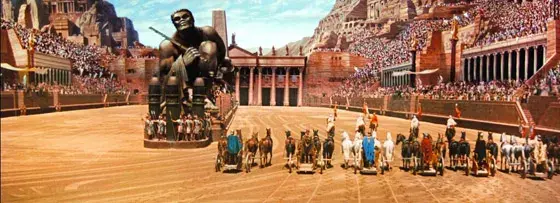

Covering 18 acres, the chariot arena was the largest film set ever built at the time. It cost $1 million to build (about $10 million today) and took 1,000 workers more than a year to construct the track alone (this doesn’t count the towering stands, backdrops, and time-accurate props – like the dolphin counter).

In addition, 78 horses were brought in from Yugoslavia and Sicily. A veterinarian, a harness maker, and 20 stable boys were employed to care for the horses and ensure they were outfitted for racing each day. A fleet of 18 chariots were built, each weighing 900 pounds. Heston even spent three hours every day learning how to ride a chariot. All of this just for one scene!

And, let me tell you, it pays off. Though the entire thing is just a blip in this near 4-hour movie, the chariot race employs no CGI and no special effects. It’s stunning what this crew was able to do using real actors, real horses, and a few lifelike dummies.

Unfortunately, Ben-Hur loses steam after the chariot race. It takes another 1.5 hours for the film to reach its conclusion. The only thing left to wrap up at this point is the crucifixion, and we take our sweet time getting there.

And, if I’m gonna be brutally honest, I don’t even think this film needed the Jesus Christ story at all. Though we begin and end with his birth and death, Jesus is largely absent from the entire movie. When we do see him, it’s from a distance or shot from behind – we never even see his face! The actor who played him, an opera singer named Claude Heater, wasn’t even credited. While Ben-Hur’s early interactions with Jesus were meaningful, we didn’t need the crucifixion to cap it all off. We all know what happens. Ending it there made this feel like a Jesus movie, not a Ben-Hur movie.

But the film was a towering success nonetheless, It was the fastest-grossing, as well as the highest-grossing, film of 1959, becoming the second highest-grossing film in history at the time, after Gone with the Wind. It won a record 11 Academy Awards (a record only matched by Titanic and LOTR: The Return of the King so far) and was number one at the US box office for six months after its release. With a $15 million budget, the film brought in $146 million on its initial release and single-handedly saved MGM from financial ruin.

So, is it worthy of all the monumental praise and accolades bestowed upon it by audiences and critics alike? Maybe. Maybe not. But that doesn’t mean it’s a movie to be passed over, either. Ben-Hur is a piece of cinema history, a grand epic in every sense of the phrase. Like others in its class, namely Gone with the Wind, it’s a movie that deserves to be seen for all its positives as well as its negatives. It’s a movie that shows us how far we’ve come from a technical standpoint, but also what we’ve lost along the way. How often do we watch something now and proclaim, “how did they do that?” We know the answer already. But Ben-Hur leaves us wondering – and that is the true definition of “movie magic”.

The Diary of Anne Frank

Director: George Stevens

Starring: Millie Perkins, Joseph Schildkraut, Shelley Winters, Richard Beymer, Gusti Huber, Lou Jacobi, Diane Baker, Douglas Spencer, Dodie Heath, Ed Wynn, Orangey the Cat

Oscar Wins: Best Supporting Actress (Shelley Winters), Best Art Direction (Black and White), Best Cinematography (Black and White)

Other Nominations: Best Supporting Actor (Ed Wynn), Best Music (Music Score of a Dramatic or Comedy Picture), Best Costume Design (Black and White), Best Director, Best Picture

Released just 14 years after the Holocaust ended, The Diary of Anne Frank tries to bring to life what was arguably one of the most popular books of the century. By the time the movie hit screens, The Diary of a Young Girl, the published diary from which the film is based, was not only a bestseller, it was available in 70 languages and had already inspired a Pulitzer Prize-winning stage production. There wasn’t a man, woman, or child who hadn’t heard of Anne Frank.

Even today it’s hard to find a middle or high schooler who hasn’t read her book. Particularly interesting to read in today’s times of COVID lockdowns and the monstrosities happening in the Middle East, Anne Frank’s story stands as an optimistic beacon, a story of empowering strength and unbelievable odds. It offers hope – however true or false it may be – that, despite everything, people really are good at heart.

Unfortunately, the same cannot be said for The Diary of Anne Frank, a Hollywood retelling that’s dragged down by poor casting, weird cinematography choices and simply being way too long. Everything possible is done to try and keep the action moving within its cluttered space, yet there are too many moments when the film lags and the dialog becomes forced. Unlike the stage production, the film leaves too little to the imagination.

1942. Hitler has invaded Holland. Several members of several families of Jewish heritage are forced to hide out in the attic of a spice factory, including Otto Frank (Joseph Schildkraut), his wife Edith Frank (Gusti Huber), and their two daughters Margot (Diane Baker) and Anne (Millie Perkins). Sharing the space is the Van Dann’s (Shelley Winters and Lou Jacobi), along with their teenage son, Peter (Richard Beymer) and his cat, Moushi.

They’re all instructed to maintain strict silence during daylight hours while the factory is filled with workers. Suspenseful in a book, boring in a movie. These scenes, which include Peter playing with his cat, Otto schooling Anne and Margot and Mrs. Van Dann kitting, give The Diary of Anne Frank a slow start.

Things pick up slightly when the strain of confinement cause arguments between the Van Dann’s, as well as Anne and her mother. The arrival of another person, a Jewish dentist named Albert Dussell (Ed Wynn) also stirs the pot, as he recounts the dire conditions outside, in which Jews suddenly disappear and are shipped off to concentration camps.

Two years pass – both in the film and in real life because this movie is LONG – and romance begins to blossom between Anne and Peter. But it’s short-lived. In August of 1944, German police discover their hiding place. As uniformed officers break down the hidden entrance, Otto declares they no longer have to live in fear, but can go forward in hope.

All in all, The Diary of Anne Frank is – in a word – safe. An unrealistic romance helps create a diversion from the horrors happening outside. There’s a whimsical, almost comical, feel to many of the scenes – suggesting life in the attic wasn’t nearly as bad as Anne made it out to be. Even the attic itself seemed huge in some scenes, with heads of the studio press-ganging the director to shoot in a Cinemascope format. Any feeling of claustrophobia is lost in these compositions that make the attic space seem luxurious.

The cast is also a bit messy. Both Ed Wynn and Shelley Winters were the sole acting nominees from the film, with Winters winning her category. Yet neither actor even TRIED to have an authentic accent. This wouldn’t bother me so much if all the actors used the same accent – even if it was American or British – but they all sounded different. Shelley Winters sounded like she came straight from New York. Ed Wynn used his Britishy Cowardly Lion-esque inflection. Everyone else either spoke with a semi-British accent or the classic trans-Atlantic accent.

Strangely the actor who gave the most memorable performance was Schildkraut. Reprising his role as Otto Frank on stage, Schildkraut brings dignity and wisdom to the role of father, as well as a deep sadness and love for Anne that makes his final scene where he returns to the hideout after the war a moment of true pain and compassion. He looks just like the real Otto Frank, too, and is one of the only ones to commit to fine-tuning his accent and inflection to sound authentic.

Director George Stevens, who led a US Army Film Unit into Dachau to document the atrocities of the Holocaust, was on hand to film the liberation of Dachau in 1945. Transformed by his experience in the war, he decided to adapt The Diary of Anne Frank as a passion project. While it’s by no means an accurate retelling, it still continues to move audiences decades after its release. Perhaps it’s one of those that’s ripe for a remake or reimagining – maybe with a little Palestinian child documenting their experiences in the Middle East…locked in an attic, praying for a peaceful conclusion to a fight that never seems to end.

Room at the Top

Director: Jack Clayton

Starring: Simone Signoret, Laurence Harvey, Heather Sears, Donald Wolfit, Donald Houston, Hermione Baddeley, Allan Cuthbertson, Raymond Huntley, John Westbrook, Ambrosine Phillpotts, Richard Pasco, Beatrice Varley, Delena Kidd, Ian Hendry, April Olrich, Mary Peach, Anthony Newlands, Avril Elgar, Thelma Ruby, Paul Whitsun-Jones, Derren Nesbitt

Oscar Wins: Best Actress (Simone Signoret), Best Writing (Adapted Screenplay)

Other Nominations: Best Actor (Laurence Harvey), Best Supporting Actress (Hermione Baddeley), Best Director, Best Picture

“Joe…be gentle with me.”

It’s easy to imagine this demure invitation to premarital sex getting some hootin’ and hollerin’ in British theaters in 1959.

The poster for Room at the Top promised “A Savage Story of Lust and Ambition”. And, indeed, the film is sultry, to say the least. There’s adultery, sex for pleasure, a man sleeping with a woman much older than him, and it even stars a French actress!

But Room at the Top is also one of the most emotionally devastating film ever created in the UK, one that genuinely changed British cinema forever.

Often cited as the first movie in the new British New Wave movement – which centered on stories about the struggles and miseries of the working class – Room at the Top set the bar for what would be come to known as “kitchen sink realism”, or a naturalistic, gritty depiction of the lower classes. These “woke” screenwriters and directors refused to paint life in the lower class as quaint or nostalgic, and instead focused on the gritty details of everyday life in tiny claustrophobic apartments where kitchen sinks were in full view.

The British New Wave films also featured groundbreaking sexual frankness in which relationships between men and women were stripped of glamour and romance. Seeing couples in bed together certainly shocked audiences, but witnessing their candor and honesty made them relevant to a younger generation that rejected middle-class morality.

Our smoldering, ambitious young hero is Joe Lampton (Laurence Harvey), a working-class Yorkshireman with a chip on his shoulder and a burning desire to work up the corporate ladder. But Joe has no interest in working hard or impressing his boss – his plan for a corner office is to bed Susan Brown (Heather Sears), the daughter of the wealthy businessman in charge.

Though Susan is romantically involved with someone else – someone of her class and social ranking – she can’t help but be wooed by Joe’s sexual charisma. Her parents do everything in their power to put this working-class lad back in his place, but Susan remains smitten.

Matters get even more complicated when Joe begins another affair with Alice Aisgill (Simone Signoret), a lonely French émigré a decade older than him. She’s unhappily married to George (Allan Cuthbertson), a privileged snob and serial adulterer who throws his affairs in her face.

Though Joe initially uses Alice just to pass the time between wooing and sleeping with Susan, he soon succumbs to the very real, deep-seated passions of their affair. He quickly comes to the conclusion that his future lies with Alice, corner office be damned! But Joe’s plans are thrown into disarray when Susan reveals she’s having Joe’s baby. Susan’s father offers Joe a job at his firm, along with a generous salary…all he has to do is stop seeing Alice and marry Susan.

Can Joe leave Alice, arguably the only woman he’s ever loved, for the life he set out to create for himself? What happens when everything we’ve ever wanted comes at the price of losing the one person who means the most to us? Is life at the top really worth leaving yourself behind?

Room at the Top skewers the class system, not just the upper classes. It not only criticizes a system that produces a sense of entitlement of the privileged, it also exposes the negative effect of the working and lower classes. When Joe mispronounces “brassier”, others in his middle-class crowd of friends laugh at him. Angered at them, Joe insists that he’s proud to be from the working class, but he really isn’t. He’s not defending his class, he’s being defensive about it. Every decision he makes in this film is done to maneuver and manipulate his way out of the working class, a point made by his uncle who questions whether Joe really wants Susan, asking, “you sure it’s the girl and not the brass?”

Though Joe also hates the members of the wealthy class, he longs to be one of them because, as part of the working class, he’s been conditioned to want what the upper crust has and to look down on his background. Joe will never find peace of mind – or satisfaction, for that matter – because the class system won’t let him.

Though set in a very specific time and place (post World War II England), the themes in Room at the Top are timeless: class struggles, moral concessions, the intricacies of love and sex, and toxic masculinity – though that term wouldn’t have that name until the 1980s. Joe’s desire for both women symbolize what society tells men is important: Susan for capital, Alice for property. His behavior, repugnant as it is, is excused because hey, he’s just a guy! When Alice asks him what it is he actually wants, he scoffs. “You know what Joe wants…it’s the same thing all the Joe’s want.” And the cycle continues…

The Nun’s Story

Director: Fred Zinnemann

Starring: Audrey Hepburn, Peter Finch, Edith Evans, Peggy Ashcroft, Dean Jagger, Mildred Dunnock, Beatrice Straight, Patricia Collinge, Rosalie Crutchley, Ruth White, Barbara O'Neil, Margaret Phillips, Patricia Bosworth, Colleen Dewhurst, Stephen Murray, Lionel Jeffries, Niall MacGinnis, Eva Kotthaus, Molly Urquhart, Dorothy Alison, Jeanette Sterke, Errol John, Orlando Martins

Oscar Wins: No wins.

Other Nominations: Best Actress (Audrey Hepburn), Best Cinematography (Color), Best Music (Music Score of a Dramatic or Comedy Picture), Best Director, Best Writing (Adapted Screenplay), Best Film Editing, Best Sound, Best Picture

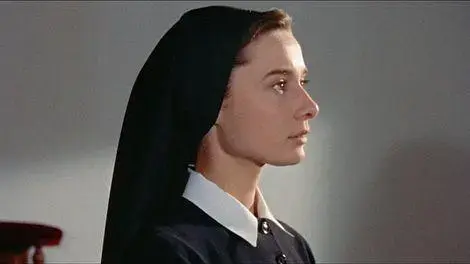

Throughout movie and TV history, we’ve seen all kinds of nuns. There have been loveable nuns, strict nuns, amusing nuns, lovesick nuns, dancing nuns and even flying nuns. But the aptly titled The Nun’s Story is perhaps the closest Hollywood has come to considering what it really means to choose a religious life. While it may seem like Catholic nuns have it easy, The Nun’s Story proves otherwise. Theirs is a life of sacrifice and surrender to God. Days are spent in silent prayer. Hair is covered. Hands are covered. There are no mirrors, no distractions, no vices, no pleasures. You’re stripped of everything you owned, everything you were. Not for the faint of heart.

Categorically, The Nun’s Story is a “women’s picture”, one of the many films released between 1930 and 1960 that explored a (white) woman’s psyche during a key chapter in her life. In these films, women are depected as their own person rather than as an accessory to a man. For Gabrielle van der Mal (Audrey Hepburn), it’s percisely this quality that makes her a poor fit for the convent.

As the daughter of a world-renowned surgeon, Gabrielle has inherited her father’s knack for medicine. She joins a religious order because it will give her the opportunity to travel the world, treating the sick and poor. Her father (Dean Jagger), who supports her decision to become a nun, can’t help but think it will be a difficult journey for her, due to her independent mind (like another famous nun, she’s a flibertyjibbit, a will-of-a-whisp, a clown…).

In the convent, Gabrielle has a hard time with the practice of silence and adjusting to the fact that she must give up all her worldly possessions and any semblance of a personal life. Though she finds academic success in nursing school, she also suffers from perceived sins of pride, along with a headstrong mindset that goes against everything a Catholic nun stands for. Yet, she perservers. Eventually, Gabrielle becomes Sister Luke and is sent to a school in Antwerp to refresh her skills as a nurse and learn more about tropical medicine. Her deepest desire is to go to the Congo to work there, but her patience and pride are constantly being tested.

For example, when one of the sisters says that she’s jealous of Sister Luke’s medical education, Mother Superior suggests Sister Luke purposefully fail her exam for the Congo to soothe her classmate’s wounded ego. Naturally, she refuses. Even though Sister Luke scored 4th highest in her class, her Congo trip is rejected and she’s sent to work in a mental asylum instead.

When she’s FINALLY sent to the Congo, she is confident that she will be serving the poor natives; however, she’s assigned to work with Dr. Fortunati (Peter Finch), the surgeon at the white hospital. Though it’s not exactly what she wanted, she’s at least closer than she’s ever been. Sister Luke throws herself into her work, exceeding the hours of her workaholic boss. When she falls ill from sleep deprevation and stress, the doctor tells her that her exhaustive inner battle with herself over issues of pride, obedience, and perfectionism is unhealthy. He’s right…and she knows it.

When circumstances take Sister Luke back to Europe in the midst of World War II, the war puts too much pressure on her commitment to the vocation. She cannot forgive the enemy and defies a mandate to remain neutral in the struggle. In the end, she must decide for herself which calling is worth fighting for.

While I thought this movie was pretty solid overall, there were parts of The Nun’s Story that were lacking – namely why Sister Luke was so obsessed with the Congo. She wouldn’t shut up about it – but we never learned why she wanted to go there so badly. Just having that background would have helped us rally behind her a little more, which would have been nice because – honestly – she’s kind of hard to like. Nothing against her character or anything, she just never talks! We know nothing about her. Just having that tiny glimpse into her brain would allow us to better sympathize with her pain and frustration as all the roadblocks kept blocking her path.

As Sister Luke, Audrey Hepburn is beautiful (as always). With not a drop of makeup on her, Hepburn is the very model of natural beauty. She offers a transparent performance in every sense of the phrase and does her best to add a personal touch to the role she considered her favorite of all her films. Indeed, Hepburn’s entire filmography shows us an actress drawn to roles focused on reinvention (My Fair Lady, Roman Holiday), but maybe her most personal was the one Gabrielle van der Mal makes from being a woman at war with herself to one accepting who she really is.

Comments