Best Picture Movie Marathon, Part 37

- melissaryanconner

- Jul 29, 2021

- 21 min read

Updated: Jan 1, 2022

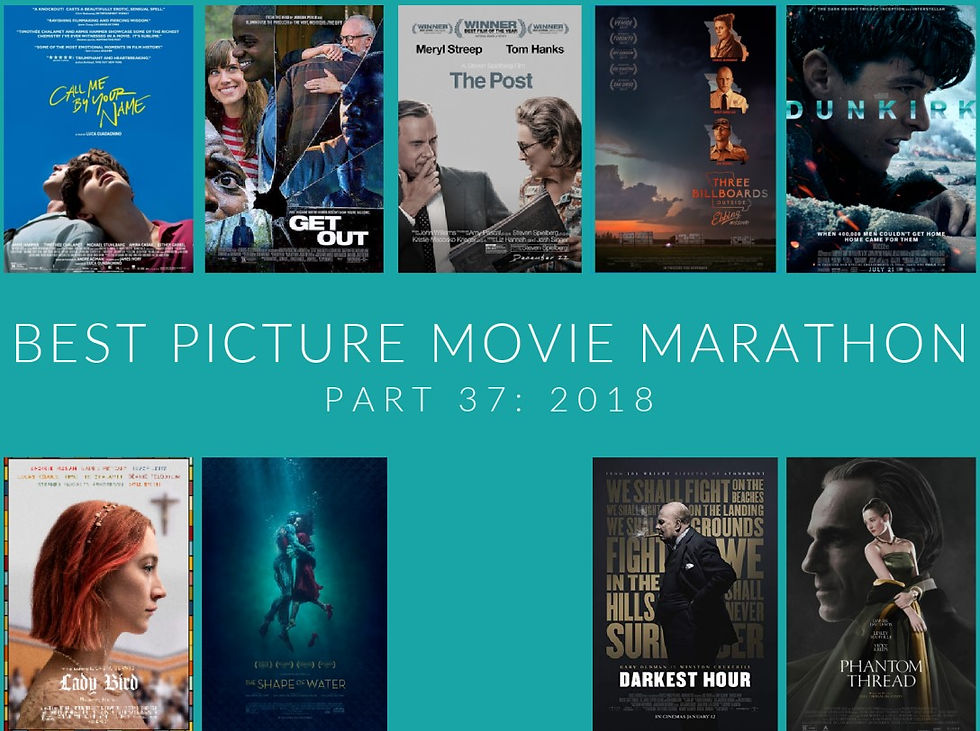

Part 37: 2018

MOVIES:

Lady Bird

The Shape of Water (winner)

Call Me By Your Name (hidden gem)

The Post

Get Out

Darkest Hour

Thee Billboards Outside Ebbing Missouri

Phantom Thread

Dunkirk

Lady Bird

Christine McPhearson (Saoirse Ronan), who prefers to be called Lady Bird, is a senior at a Catholic girls’ high school. After reading her college application essay, the principal, Sister Sarah Joan (Lois Smith) says, “It’s clear how much you love Sacramento.” This comes as a surprise to Lady Bird, and us as viewers, since we’re all too aware of how frustrated Lady Bird is with her hometown.

“I guess I just pay attention,” Lady Bird replies.

“Don’t you think they’re the same thing?” the wise sister says.

The notion that attention is a form of love becomes a key aspect of the film, Lady Bird. Taking place during the 2002/2003 academic year, this coming-of-age story requires you to pay it attention…to take notice of its melodies, both sung and unsung. And, if you do that, you will most certainly love it.

It’s on a college road trip where Lady Bird confesses to her mother, Marion (Laurie Metcalf) that she desires to leave Sacramento (the “Midwest of California”, as she calls it), and go to college out East, “where the culture is.” All too aware of the financial burden of sending her daughter to New York, Marion shoots that shizz down. Forced to work double shifts after her husband, Larry (Tracy Letts) is laid off, she sternly informs Lady Bird that she will attend an in-state college, whether she likes it or not.

Like most coming-of-age stories, this push and pull between mother and daughter is the energy that drives this film forward, though the heart of it lies not so much in the relationship between Lady Bird and her mother, but in the space between them. Lady Bird wants nothing more than to satisfy Marion, which is a difficult task because the standards seem impossibly high. She also wants to be true to herself and yearns for her mother to accept her the way she is, which seems closer to impossible than anything. “Do you like me?” she asks Marion in a moment of weakness. “Of course I love you,” Marion replies. “Yeah, but do you LIKE me?” Ugh, heartbreaking.

Chances are most girls will find echoes of their own life in Lady Bird. After all, this is a teenage story. Homecoming, prom, math tests and school plays…the agonizing stages of finding a college. We’ve all been there, or are venturing there shortly. Along the way, Lady Bird undergoes other rites of passage: falling love, losing her virginity, realizing what true friendship means. It’s all the most relatable stuff.

The cast of characters looks all too familiar, too. There’s the best friend, Julie (Beanie Feldstein), the first boyfriend, Danny (Lucas Hedges) and the first sexual awakening, Kyle (Timothee Chalamet). There’s the mean girl at school, Jenna (Odeya Rush) and the meaner, older brother, Miguel (Jordan Rodrigues). You may think you’ve seen this all before, and you probably have – but not like this.

What director Greta Gerwig accomplishes in Lady Bird is that she infuses one of the most conventional, rose-colored genres with freshness and surprise. Though these characters may look like they’ve been copied and pasted from a John Hughes story, they’re given more depth in Lady Bird. They all have their own struggles, their own personal demons, their own battles that they’re trying to brave. And, as Lady Bird comes to learn, no one has it easy. Whether it’s Julie’s problem with weight or Larry’s inability to find a job, we all struggle.

Growing up means different things to different people. Experiences we have as teenagers sometimes mean everything, then something, then nothing. But they inevitably become the moments that shape us, that mold and form our opinions of ourselves and the world at large. With great hilarity and wit, Lady Bird shows us that growing up is scary, fun, sexy, challenging, and heartbreaking all at once. No matter what our lot in life, no one escapes unhurt or unharmed, and there seems to be great comfort in that.

The Shape of Water

It seems that only a director like Guillermo del Toro could make you root for a woman to get it on with a scaley fish-man who eats cats.

In this love letter to the lonely, The Shape of Water holds dream, nightmare and realism in perfect balance. Though it begins like a fairy tale, with words like ‘monster’, ‘love’, and ‘princess’ in the opening monologue, The Shape of Water takes place in the real world – 1962, in fact. Actually, it was probably a time that felt very much like a fantasy to those who experienced it. The Space Race was in full swing, the Cold War was underway and the palettes that would come to define mid-century modern décor turned every living room into a groovy escape.

But for Elisa (Sally Hawkins), life is quiet…quite literally. A mute since childhood, Elisa uses sign language to communicate with the few people she lets into her life, including her artistic gay neighbor, Giles (Richard Jenkins) and her co-worker, Zelda (Octavia Spencer).

Deep in the cavernous underground tunnels of the OCCAM Aerospace Research Facility, Elisa and Zelda spend their time mopping floors and taking out garbage. The two have a sweet friendship, cemented in the fact that Zelda fills up the quiet with her running commentary on her life and makes it a priority to learn sign language so she can communicate with Elisa.

Whatever is done at OCCAM is top secret and everyone is paranoid about moles, especially when the lab takes possession of an amphibious creature from the Amazon, known as “The Asset”. Once worshiped as a god, this creature now endures torture from the head honcho of OCCAM, a sadist racist named Strickland (Michael Shannon). The scientist tasked with researching the creature (Michael Stuhlbarg) begs for mercy, but Strickland won’t hear it. SOMEONE has a complex.

Meanwhile, Elisa finds herself drawn to the “monster” and slowly begins courting him. She brings him food. She plays him Benny Goodman records. She teaches him sign language (which he appears to pick up VERY quickly). Thus, a romance builds…and quite cleverly, I might add.

The fact that both Elisa and the creature are silent puts them on even footing. If she could speak, her attempts to converse with him might make him seem like a pet. But because they both communicate through action, they’re equal. They build their connection through sign language, body language and music. In many ways, it’s a relationship built very much on the things that unite all humans, regardless of skin color.

Filmed in aqueous greens and blues, The Shape of Water feels so saturated that you can almost smell the dank rot in those basement corridors. The whole film has a clammy wet mood, as if everything is underwater. Elisa’s apartment has a deep green tint. The bathrooms of OCCAM are cartoonishly green. Elisa is constantly wearing green. Even Giles works on an advertisement for green Jell-O.

Green, as we’re told many times throughout the film, is “the future”. Strickland, who lives in a home so yellowy bright that it’s almost a shock to the eyes when we see it, is clearly stuck in the past. Even his car – which is not green, but teal – is just on the cusp, wavering between yesterday and tomorrow.

These subtle color hints make this world of fantasy all the more magical. However, there are also scenes that ground us firmly in reality, such as a black couple being refused service or TV footage of a civil rights march. While these scenes certainly help compare reality to fantasy, I don’t think the film needed them. Like the love between Elisa and her creature, the story has its own way of speaking to us. After all, isn’t that the point of most fairy tales?

Though The Shape of Water sometimes sinks from its own best intentions, it’s no doubt a homage to freaks and outcasts. Like The Phantom of the Opera, this film teaches us to open up our minds, let our fantasies unwind, into the darkness that we know we cannot fight.

Call Me By Your Name

Like a first love, Call Me By Your Name sneaks up on you. You could call it an erotic film, which it is, but it’s more a film about love…the kind of love that is bigger and more frightening than we can imagine. It’s the kind of love that is equal parts passion and torment, that irrational fire that pulls you to another human being. But it’s also tender, sweet, compassionate. Holding someone’s hand for the first time. The butterflies you feel when skin brushes against skin. It is a love letter to being in love.

Elio (Timothee Chalamet) is a 17-year-old gangly boy of skin and bones visiting his family’s summer home in Italy with his parents. His father (Michael Stuhlbarg) is an esteemed professor of Greco-Roman culture and his mother (Amira Casar) is a translator.

The world Elio and his parents live in is one filled with language, stories, music and art. The food they eat is decadent. Juicy fruit trees surround them. Everyone shows bare shoulders, legs and arms. The set itself is charged with desire. And, into this garden of sensual delights, a snake comes prowling…

Elio’s parents play host to an American doctoral student named Oliver (Armie Hammer), who arrives for the annual internship Elio’s father offers. Oliver is everything Elio isn’t. Tall, gorgeous and confident, Oliver is – by definition – a hunk. Everyone seems drawn to him, including Elio.

The chemistry between Hammer and Chalamet, and their characters, is powerful right from the get-go. The spark between them takes a while to fan the flame, as they both test, push and feel each other out. As they bond over classical music and literature, a friendship blossoms. This electric connection is unmistakable. Lazy poolside chats are fraught with tension; bike rides feel like nervous first dates. Under these little bonding moments lingers a charge so strong it’s impossible not to be nervous ourselves!

It’s not until a full hour or so into the film that any true feelings are explored. And, when it happens, the moment is rife with intimacy. The emotions feel completely authentic. After 60+ minutes of watching these men slowly add fuel to their fire, seeing them finally admit to themselves, and each other, how they feel is nothing short of euphoric.

But if there’s one thing we all know about summer love, it’s how fleeting it is. Like a juicy, ripe peach, this relationship could never last forever. Though the film never makes a big deal about the 7-year age difference, there’s no denying that Oliver holds the cards in this whirlwind love affair…and this free-wheeling man of the world is not about to be tied down.

Those who describe this film as a “coming out story” are missed the point. Yes, there is a homosexual relationship in this film but the storyline never dwells on either character admitting their sexuality. As a matter of fact, everyone in this movie is extremely sexual. Both Elio and Oliver sleep with women and there are even moments when Elio’s father seems to admit his own homosexual feelings.

The terms “gay”, “bi”, and “homosexual” are never even used in the film. Though it takes place during the 1980s, there never a sense of danger about their relationship. Homophobia doesn’t even seem to be part of the vernacular. This movie is less about being gay and more about just being in love.

Towards the end of the film, Elio’s father speaks to him about love had and love lost: “Our hearts and our bodies are given to us only once,” he says. “And before you know it, your heart’s won out. And as for your body, there comes a point when no one looks at it, much less wants to come near it. Right now, there’s sorrow, pain. Don’t kill it, and with it the joy you’ve felt.” For such a simple story, Call Me By Your Name taps into our innate desires…the desire to be touched, to be held, to be understood, to be loved. Perhaps more importantly, it also taps into that guttural feeling you experience when those things are gone.

The Post

“We can’t have an administration dictating to us our coverage just because they don’t like what we print about them in our newspaper.” When Donald Trump’s White House declared war not only on the media but on “truth” itself, Steven Spielberg rushed to make a topical film that spoke to freedom of the press. But, in his hurry to make a relevant movie, he may have forgotten to make an honest one, or even a good one. Designed to be a commentary on today as much as yesterday, The Post is great at calling attention to how important it is, yet it feels too rushed, like a journalist trying to make that midnight deadline.

In the early 1970s, “The Washington Post” was a small, local paper trying to keep up with the titans. Led by Kay Graham (Meryl Streep), the country’s first female newspaper publisher, “The Post” hopes to improve its fortunes by going public on the stock market.

Meanwhile, editor Ben Bradlee (Tom Hanks) constantly prowls for any story he can find, hoping for something that can give him an edge over the competition. His luck takes a turn when “The New York Times” publishes a searing expose detailing the shocking truth behind America’s involvement in the Vietnam War. The country is rocked to its core. President Nixon bars the paper from publishing any other stories on the matter.

As “The New York Times” sits idle, waiting for its day in court, “Post” reporter Ben Bagdikian (Bob Odenkirk) stumbles upon some interesting information. He acquires a series of classified documents, known as “The Pentagon Papers”, and they reveal some devastating facts about American leadership. Kay Graham then has to make the most important decision of her career: publish “The Pentagon Papers” and fulfill her company’s obligation to the general public or hold the presses so she doesn’t endanger the paper’s future.

Given Kay’s hesitation in publishing “The Pentagon Papers”, and considering her relationship with Robert McNamara, The Post should be about her fear that she might make the wrong decision; however, the stakes she’s up against don’t always feel right. There’s a distinct lack of suspense. It seems this clean, polished version of history takes place in a Hollywood vacuum – even going so far as to cast America’s golden parents, Streep and Hanks, as the leads. The typical Spielberg ending doesn’t really help the matter, either. Where are the Kay Graham’s and Ben Bradlee’s of the world today? That’s the question I wish The Post asked more directly and angrily.

Get Out

The premise of Get Out has been done before: a black guy goes home with his white girlfriend to meet her parents. You can pretty much fill in the blanks from there.

Except, in this case, you can’t. Get Out, the directorial debut of Jordan Peele, casts this popular story about racism not as a comedy, but as a horror film. And what makes it extra chilling is that the villains aren’t rednecks or neo-Nazis. They’re not the alt-right, the skinheads, the Trump supporters or the KKK. Nope, the villains of Get Out are middle-class white liberals. The kind of people who shop at Whole Foods and Trader Joe’s, who communicate only in Beyonce memes and would have voted for Obama a third time if they could.

However as well-meaning they may think they are, Get Out shows how these white liberals actually make life hard and uncomfortable for black people. It exposes a liberal ignorance that leads to complacency, which is just as dangerous as the film’s horrific final solution.

Like most thrillers, the less you know about this story, the better. Therefore, I’m gonna keep this really simple.

Chris (Daniel Kaluuya) and his girlfriend, Rose (Allison Williams) have reached a pinnacle moment in their relationship: meeting the parents. It’s been about 5 months and Rose wants to introduce Chris to mom and dad. The only problem is she hasn’t told them that Chris is black.

Their love is color blind, but the world isn’t – and Chris is wary of how her parents might react. But he needn’t be – their reception couldn’t be warmer. Rose’s dad, Dean (Bradley Whitford) and mom, Missy (Catherine Keener) hug and welcome Chris into their home without so much as batting an eye.

Still, there’s something…off. Handyman Walter (Marcus Henderson) and housekeeper Georgina (Betty Gabriel) are a little too obedient. And the idea that a white liberal family has black help is certainly not lost on Chris. But, as we so often do in social or racial situations, Chris keeps trying to excuse their behavior. Maybe they’re jealous or skeptical of his relationship with Rose. NBD.

Meanwhile Dean and Missy pretend not to notice Chris’s skin color, all the while secretly congratulating themselves on how accepting they are. When Dean shares how proud he is that his dad ran alongside Jesse Owens in the 1936 Olympics, you get the impression he wouldn’t tell the story with half as much pride if Chris were white.

And that’s where I’m stopping because any more information would be too much information. As tension builds, Peele tells a story that perfectly weaves together utter horror and perfect comedy, then concludes with a twist that left me like a deer in the headlights.

With a budget of just $4.5 million, Get Out grossed $255.5 million worldwide. It was one of the top 10 highest-grossing films of 2017 and was deemed “a cultural phenomenon” due to the numerous memes and fan art that were inspired by the film. It earned four Oscar nominations: Best Picture, Best Director, Best Actor (Kaluuya) and Best Original Screenplay, which it won.

During the 2017 Oscar race, one anonymous voter told The Hollywood Reporter that they felt alienated by the film’s campaign: “Instead of focusing on the fact that this was an entertaining little horror movie that made quite a bit of money,” they said, “they started trying to suggest it had deeper meaning than it does, and, as far as I’m concerned, they played the race card, and that really turned me off. In fact, at one of the luncheons, the lead actor [Kaluuya], who is not from the United States, was giving us a lecture on racism in America and how black lives matter, and I thought, ‘What does this have to do with Get Out?’ They’re trying to make me think that if I don’t vote for this movie, I’m a racist. I was really offended.”

*Queue Curb Your Enthusiasm theme song.*

The target of Get Out is a brave one, probably a sizable chunk of the movie’s audience. But Peele does a great job of asking the liberal white population to just stop and do some self-examination. Because even when you swear to treat everyone the same, the experience of a black person is still different from that of a white person. It’s not up to white people to decide the state of racial equality. Yet Peele doesn’t preach or lecture. In fact, a lot of its deeper messages only bubble to the surface after two or more viewings. If you haven’t seen it, get out and go check it out. And if you have, get out and go see it again.

Darkest Hour

Between Dunkirk and Darkest Hour, 2017 was a big year for British stiff-upper-lip movies. In their own way, both films dealt with England’s crises at home and abroad during the darkest days of World War II.

In Dunkirk, we are immersed in the sights, sounds and smells of the battlefield. Darkest Hour, on the other hand, is more interested in the battles being waged back home. In the cigar smoke-filled backrooms of Parliament and 10 Downing Street, Winston Churchill (Gary Oldman) is fighting his own political battles to face down Hitler and prevent the Nazis from overtaking Britain.

It’s May 1940. The countries of Western Europe are falling like dominos to the Nazis. Three million German troops have reached the Belgian border in the Invasion of France and Britain is next.

Meanwhile the British parliament is losing faith in prime minister, Neville Chamberlain (Ronald Pickup). Reluctantly, the Conservative grandees hand the top job to Churchill.

Controversial and larger than life in every way, Winston Churchill made catastrophic mistakes during World War I and his placement as prime minister causes doubts among his peers. Even King George VI (Ben Mendelsohn) questions whether Churchill is the man for the job.

But the Brits have no choice. It’s Churchill or bust. While other political leaders, and much of the British parliament, try to convince Churchill to strike a deal with Hitler, Churchill adamantly refuses, a decision that affects his relationship with his peers, yet strengthens his relationship with the country at large.

Clocking in at just over 2 hours, Darkest Hour falls short of getting into the nitty-gritty of these momentous days in British history. This is a broad-strokes biopic, not unlike Steven Spielberg’s film, Lincoln. It’s painting a portrait of a great man by working in miniature. All the key moments and characters are there, including Churchill’s wife, Clementine (Kristin Scott Thomas) and his doting secretary, Elizabeth (Lily James).

And while it’s not nearly the film Lincoln was, or Dunkirk was for that matter, it still has a wonderful central performance from Gary Oldman…one in which actor disappears into character…and one that would earn Oldman is first Oscar.

Though Churchill is the center character here, Darkest Hour is by no means a wholly flattering portrayal of the man. Because he was so brash and well-loved by Britain at large, it’s easy to assume that his policies were the right ones. However, this film isn’t so sure. Churchill’s rants about “fighting to the last man” seem dangerously fanatical and parliament’s talks of peace don’t sound completely out of the question. This film is great at not taking sides and it’s the better for it.

That being said, the movie isn’t nearly as good as Oldman’s performance. It’s long and it feels long. Some bits are hard to understand (mostly due to a combination of thick accents and mumbling) and the lack of action causes this political thriller to drag a bit. Yet it ironically serves as a wonderful companion piece to Dunkirk, whether that was planned or not.

Well-loved by the Academy, Darkest Hour received six Oscar nominations, winning Best Actor (Oldman) and Best Makeup and Hairstyling. Oldman also won the Golden Globe for Best Actor, the BAFTA Award for Best Actor and the Screen Actors Guild Award for Outstanding Performance by a Male Actor in a Leading Role. Can I get a V for Victory?!

Like House of Cards, Darkest Hour takes us behind the scenes of political warfare – where artillery is replaced with oratory and the battlefield is nothing but a chess board, reeking of whiskey and smoke.

Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri

How can we not be angry at an unfair world? Life will take children before parents. It will give cancer to young, healthy people. It will put vulnerable children in horrible situations. Life can be racist, sexist and cruel.

There are those who find it easier to process anger than others. Some try therapy or journaling. Some get it out with exercise or supporting a cause they like. But others find comfort in fighting back, in yelling and screaming at a world that is unjust. For those folks, anger is not something to be cured but a path on the road to comprehension.

One such person is Mildred Hayes (Frances McDormand). Mildred is angry for a multitude of reasons. First, she’s recently divorced, her ex-husband having left her for a much younger woman. Second, her daughter Angela was raped and murdered less than a year ago and third, her case has gone cold.

In an effort to keep Angela’s case in the public eye, Mildred rents out three billboards on a road out of town, writing a pointed message directed towards the police department tasked with tracking down Angela’s murderer:

RAPED WHILE DYING

AND STILL NO ARRESTS?

HOW COME, CHIEF WILLOUGHBY?

Chief Willoughby (Woody Harrelson), who has problems of his own, takes the whole thing more or less in stride, but one of his cops, Officer Dixon (Sam Rockwell) takes it to heart. While Mildred’s billboards make regional news and stir up the small town of Ebbing, Missouri, Dixon goes off the deep end, trying to bully Mildred into backing off.

But Mildred isn’t one to back down. As the whole situation escalates, the town of Ebbing becomes a hotbed of hatred, racism, anger and rage. With no leads, Mildred takes her daughter’s case into her own hands – finding her own ways of motivating local law enforcement to track town Angela’s killer.

Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri is set up to have us questioning everyone. Though she’s a bonified McDormand-style ass-kicking character, Mildred isn’t what you would call “likeable”. She’s not a good mother, having little to no respect for her son (Lucas Hedges) and takes advantage of those trying to help her, including James (Peter Dinklage) who still finds something attractive in this hardened woman.

Alongside her story is that of Officer Dixon, a racist with a low IQ who is basically everything you don’t want in a police officer. He performs horrible, violent acts of rage, yet is given a bit of a redemption arc that may have some viewers defending him.

The film also introduces so many plot points in order to tell a bigger story, but many of them just get lost in Mildred’s story – which is already too big. Certain characters, like Chief Willoughby, got storylines that didn’t add much of anything to the main story, while other characters, like Mildred’s son Robbie, are just begging for more development.

Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri received seven Oscar nominations, including Best Picture, Best Actress (McDormand), Best Original Screenplay and two Best Supporting Actor nominations (Rockwell and Harrelson). Both McDormand and Rockwell took home their respective awards.

I have to be honest, this was one of those films I liked a lot the first time I saw it, then liked less after watching it again. Look, I’m all for a good anti-hero, but both Mildred and Dixon failed to win my sympathy. Even Walter White, arguably the best anti-hero ever created, had some redeeming qualities. In the end, I just didn’t care what happened to these characters, and really the movie didn’t care, either. The ending felt unrewarding, unresolved and, like Angela’s case, forgotten.

Phantom Thread

Paul Thomas Anderson’s movies are fueled by hunger. Boogie Nights – the hunger for fame. Magnolia – the hunger for reconciliation. There Will Be Blood and The Master – hunger for legacy. Punch-Drunk-Love – well, love (and pudding). These characters delight in starving themselves for what they desire most, then are more often than not rewarded for it at the end.

But Phantom Thread has a much more literal hunger on its mind. This gothic romance is driven by gluttony. In this ravenous tale of lost mothers and secret messages, a man indulges in every aspect of his life, oftentimes to his own detriment.

In what he has claimed to be his final performance, Daniel Day Lewis plays fashion artist Reynolds Woodcock, an obsessive man with an Oedipus complex. He specializes in making extravagant dresses with the finest silks and fabrics, following in the footsteps of his dearly departed mother.

Much like the art he works so tirelessly to perfect, Reynolds likes every stitch in place - both professionally and personally. He moves the people in his life around like chess pieces, always in control.

On a trip to the country, Reynolds meets Alma (Vicky Kripes) a waitress who impresses him by memorizing his ridiculous breakfast order ("Welsh rabbit with a poached egg on top, bacon, scones, butter, cream, jam [not strawberry], lapsang tea, and some sausages.”). And just like that, Reynolds has found his muse. As Reynolds and Alma circle each other, figuring out their dynamic by testing each other’s boundaries, a weird and bizarre relationship begins to form.

On the outside looking in is Reynolds’ sister and business partner, Cyril (Lesley Manville), who acts as a kind of gatekeeper between her brother and his disposable muses. She’s creepy and macabre, not unlike the housekeeper from Rebecca – always hovering, always lurking, and the damn master of the side-eye.

With insect-like limbs, a gaunt face and a shaky British/Transylvanian accent, Reynolds almost looks like a vampire. His clothes are dark and gothic, even his home is shot in cool shades of blue and gray. While he’s not hungry for blood in the literal sense, his insatiable appetite becomes his tell when he’s aroused. With time, Alma learns how to satisfy her “hungry boy”, as she begins to crack through the walls of Reynolds’ hard outer shell.

Weaving together beautiful set designs, a stunning musical score and – of course – amazing costumes, Phantom Thread is a treat for all the senses. It’s warm and comforting, like a bowl of cassoulet, but also cold and off-putting at the same time. You somehow feel both welcomed and on-edge; open, yet skeptical. With performances that are Hitchcockian in nature, Phantom Thread is up there with the likes of Rebecca and Gaslight as a fascinating character piece that is sure to wet your appetite.

Dunkirk

It finally looked like the beginning of the end for World War II. In the last week of May 1940, more than 300,000 British soldiers were beaten back to the beaches of Dunkirk by the German troops.

A small coastal town at the northernmost point of France, Dunkirk wasn’t a great place to be pinned down. The harbor was so shallow that the large British naval ships couldn’t get close enough for a rescue. The men on the beach were stranded, sitting ducks waiting for either deliverance or death. But perhaps the cruelest irony of all was that they could actually see the coast of England, just 26 miles across the channel. Home was so close, yet so far.

From that seemingly hopeless situation came one of Britain’s finest moments of the war. In an effort to bring their boys home, countless civilians assembled a fleet of non-military pleasure boats and set sail across the channel to evacuate the soldiers. This race-against-the-clock mission, and the days leading up to it, is the subject of Christopher Nolan’s epic, Dunkirk.

From the very start, we’re thrown into the chaos and terror of war. Tommy (Fionn Whitehead) scrambles desperately to run to the beach, all while dodging enemy fire from the streets of Dunkirk. He eventually arrives, only to be greeted by thousands of stranded French and British soldiers. Corpses are being buried in the sand. With no cover, German soldiers are attacking from the sea and from the air. A high-ranking naval officer (Kenneth Branagh) watches the nightmare from a pier, practically willing a ship to appear with his eyes locked on the horizon.

Meanwhile, RAF pilot Farrier (Tom Hardy) is, in fact, engaging the enemy overhead. With a broken fuel gauge, Farrier is taking major risks by staying in the air, but he refuses to lose sight of the German planes circling the boys on the beach.

Back on the home front, Mr. Dawson (Mark Rylance), is gearing up to take his little fishing boat to Dunkirk, joining the people’s armada in an effort to bring British soldiers back home. Along the way, he rescues a traumatized officer (Cillian Murphy) and endures a terrible tragedy that threatens his mission.

Like most Nolan films, Dunkirk plays around with time. The evacuation is told through three subplots, each lasting a different amount of time: land (a week), sea (a day) and air (an hour). The movie then hops between them in ways that compress and expand time for poetic effect.

It’s also a film told without names, and with long stretches of no dialogue. Shell-shocked soldiers are too scared to speak, ear-splitting explosions and the deafening scream of dive bombers fill our ears with the terrible sounds of war. Through claustrophobic scenes and a tick-tock score by Hans Zimmer, the cinematography and music feel like an additional enemy front, adding suspense and heart-racing tension to a film that already has us on the edge of our seats.

As of today, Dunkirk is the highest-grossing World War II film (not adjusting for inflation) of all time, making $526 million worldwide. It received eight Oscar nominations, winning three: Best Sound Editing, Best Sound Mixing and Best Film Editing.

Unlike most World War II films, we never see the Germans in Dunkirk. Nolan’s goal was to give an exclusively British account of events, zeroing in on how it must have felt to those soldiers, pilots and civilians who lived it. This inspiring story of the little ships was something many in Britain grew up with, almost like a fairy tale. While the ‘Dunkirk Spirit’ may be more familiar in the UK than here in America, that’s certainly no obstacle in telling this story. The film resonates on a very human level, revealing that fear can take many different forms, as can heroism.

コメント